In recent months the Government of Uganda (GoU) has taken important steps to reclaim its electricity system from private interests. The World Bank had for many years become fond of presenting Uganda as a shining example of the benefits of privatisation, but in its latest move the GoU has decided to not extend the 20-year Concession Contract with the private power distribution company Umeme Limited.

It is expected that Uganda will form a state-owned electricity distributor (the National Electricity Company) or ask the Uganda Electricity Distribution Company Limited (UEDCL) to take over. UEDCL is the official owner of the distribution network, but was effectively sidelined in 2005 when the concession with Umeme came into effect.

The contract with Umeme has provoked national outrage for well over a decade, and has been the subject of at least one parliamentary inquiry into overcharging, corruption and underinvestment. The renationalisation of the distribution system follows Uganda’s 2022 decision to not renew its power purchase agreement (PPA) with Eskom Uganda. The country has also announced it will stop the use of “take or pay” (ToP) contracts with private generation companies (known as Independent Power Producers, or IPPs). ToP contracts allow IPPs to be paid regardless of whether the electricity is used or not, which is costing Uganda (and many other countries) huge amounts of money while benefitting for-profit interests.

Uganda’s actions are part of a pushback on the part of a growing number of Global South governments against the systematic undermining of public electricity systems that began in the 1990s during the World Bank and IMF-led structural adjustment period.

The pushback against neoliberal reforms continues to face many obstacles, but it makes visible possibilities to reclaim and restore the continent’s public energy systems, a policy which a growing number of the region’s trade union bodies support, including the African Regional Organisation of the International Trade Union Confederation, ITUC Africa.

In August 2025, unions and allies from across the continent will gather in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, for a campaign-focused Energy Justice for Africa working meeting co-convened by ITUC-Africa and TUED South. The principal goal of the Dar es Salaam meeting is to clarify and popularise support for a public pathway approach to energy transition while addressing energy scarcity, crippling levels of debt, and neocolonial exploitation of the continent’s natural resources by foreign capital. (The meeting will be covered in future TUED bulletins).

According to ITUC Africa’s General Secretary, Joel Akhator Odigie, “Africa’s unions have known all along that the ‘privatise to decarbonise’ message peddled by the World Bank would come to nothing. Today more than 600 million people in Africa do not have access to basic electricity. But we export almost 60% of our gas to rich countries in order to service debt to foreign banks. Unions are not simply demanding a new approach, we are currently developing a set of energy and climate-related proposals that will resonate across the continent and beyond.”

In April 2024, the World Bank Group launched its Mission 300 – what it describes as “an ambitious effort to provide at least 300 million people in Africa with electricity access by 2030.” For Odigie, “The Bank states that ‘massive private investment is crucial’ and ‘businesses must step in and scale up investments.’ But it’s not going to happen. In 2016, the Bank launched its New Deal on Energy for Africa. It was supposed to ‘mobilize’ private investment to achieve 100% electricity access in urban areas and 95% access in rural areas by 2025. The initiative was a total failure.” The extent of the failure has been documented in the TUED South position paper, Reclaim and Restore: Preparing a Public Pathway to Address Energy Poverty and Energy Transition in sub-Saharan Africa. The position paper has been endorsed by ITUC Africa’s 5th Quadrennial Congress in November 2023, 12 national centres, as well as by individual unions.

Commenting on the situation in Uganda, Dr Everline Aketch, Public Services International’s Sub-regional Secretary for English-Speaking Africa, told TUED: “The Eskom and Umeme contracts had been running since 2003 and 2005 respectively; they will not be renewed. The news was received with joy and relief, not only because of the poor performance of these companies—frequent power outages and high tariffs—but also due to costly private equity structures causing significant losses to taxpayers.”

However, Aketch noted, in Uganda’s case, the government’s Electricity (Amendment) Act of 2022 and the GoU’s Energy Policy for Uganda 2023 continues to entertain hopes that private investors will find the country’s power sector attractive. The GoU says it intends to “support renewable energy auctions for accelerated deployment of solar power through private sector participation.” It also wants to attract private investment to build up the country’s transmission systems.

But if recent history is any guide, the government could be waiting a very long time for the private sector to show up. Uganda may have once been a model client for neoliberal consultants, but it is also a model for neoliberal failure. A quarter century has passed since privatisation started, but the government’s own data show that the country’s electricity connectivity rate of 28% is still one of the lowest in Africa (below the Sub-Saharan average of 43%) Access in rural areas is still just 8%, also far below the regional average of 29%.

In the 2023 policy document, the GoK sheepishly admits, “some level of private capital has been attracted into the [electricity] sector, but this has come at a very high cost of financing, thus leading to high tariffs and huge buy-out amounts. This situation has raised issues of financial sustainability. With such compounded challenges, the uptake of energy products and the quality of the products have been heavily affected, including reliability.”

Uganda’s ending of “take or pay” contracts and the renationalisation of the distribution networks has been welcomed by unions who view these actions as starting points for the restoration of public energy, hopefully giving impetus to a full-on rural electrification program. But the private sector has already warned that the GoU’s actions will scare away investors. Clearly, if the GoU’s efforts to create an “enabling environment” for the private sector did not generate sufficient investment in the past, such investment is even less likely now. The GoU must therefore pull the curtain down on what has been a slow motion policy calamity, and build its energy future around a clear public approach. “Uganda’s story is emblematic,” said Odigie, “and similar battles for energy justice are unfolding across the region. Workers in Africa are ready to fight for a clear alternative anchored in new public energy systems that can provide a platform for climate-friendly development that is pro-people and can break the cycle of debt and poverty.”

Uganda’s experience with privatisation tells an important story. In 1993, the World Bank declared it would cease lending money to governments for energy projects unless those same governments committed to break up their utilities (“unbundling”), create room for private IPPs, set up a so-called “independent regulator” to keep government ministries and the utility in check, and strive to achieve “cost reflective tariffs” by raising electricity prices.

Compared to other governments in the region, Uganda went further with the reform agenda (named “the standard model” by the Bank) hoping that it would attract foreign direct investment. In 1998, the GOU commissioned London Economics International LLC (LEI), a financial consulting firm, to produce the Ugandan Power Sector Restructuring and Privatisation: New Strategy Plan and Implementation Plan. In typical neoliberal fashion, LEI attributed Uganda’s low electrification levels to an “underperforming” public utility, in this case the Uganda Electricity Board (UEB).

Referring to the 1990s reforms, a Ugandan respondent to a 2019 World Bank survey noted, “The political unrest and civil war up to 1986 left a dilapidated infrastructure with limited government resources to fund system expansion. Economic liberalisation ideology, prescribed by the IMF and World Bank, was a pre-condition for providing funding to the energy sector and for the national budget as a whole.” In other words, the World Bank saw the country’s economic woes as an opportunity to push an aggressive privatisation agenda, with the power sector being a major target.

The 1999 Electricity Act was based on the LEI report, and the legislation expedited the unbundling of UEB into three entities, the Uganda Electricity Generation Company Limited (UEGCL), Uganda Electricity Transmission Company Limited (UETCL) and UEDCL. Within two years of the Act becoming law, electricity tariffs doubled. Uganda also became the happy hunting ground for 38 for-profit IPPs who were awarded “Take of Pay” contracts that obligated the (still public) UECTL and the GoU to honor power purchase agreements (PPAs) for up to 30 years.

Currently, IPPs generate roughly 58% of Uganda’s electricity, but the levels of installed capacity remain woefully insufficient. Lucrative contracts, it seems, do not always add up to increased connectivity, particularly in rural areas. Umeme did oversee the expansion of the distribution system, but it gravitated towards industrial and commercial users. In 2023, these users account for around 70% of the company’s revenues, according to the International Energy Agency.

Nevertheless, a 2020 World Bank assessment of the impact of privatisation singled out Uganda for special praise, “Among countries in Sub‑Saharan Africa, Uganda is one of those that has gone furthest in implementing the power sector reform model of the 1990s; having completed vertical unbundling… Uganda is one of the only countries in Sub‑Saharan Africa that has a financially viable power sector.”

Defending Uganda’s contract with Umeme, a 2019 African Development Bank report welcomed the steady increase in electricity charges, noting that “Umeme received regulatory approval for several successive tariff increases from 2006 to 2012…Allowing cost-reflective tariffs ensured Umeme’s financial health.”

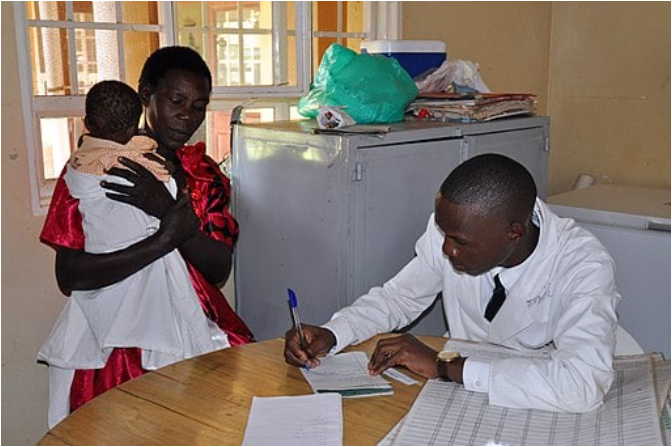

However, the report failed to mention that, in 2012, Umeme cut power to a hospital in Jinja without giving prior notice, an act that led to the deaths of 150 babies who were on oxygen concentrators. In 2015, Kiboga District Hospital (which then served 100,000 people) was without power for over a month. Umeme disconnected the supply because the government of Uganda had not paid the bill of US $26,600. According to a report by Primah Kwagala, then with the Center for Health, Human Rights, and Development (CEHURD), doctors were unable to provide even basic first aid because they could not sterilize tools. Vaccines and blood went bad because of the lack of refrigeration. The maternity wing was in complete darkness, and Cesarean sections could not be performed. Mothers died on their way to the capital Kampala or private clinics to access emergency obstetric care.

The 2005 concession contract with Umeme had already attracted criticism before the hospital deaths, with some members of parliament calling for the contract with Umeme to be annulled. According to a 2012 investigation conducted by the Ad hoc Committee on Energy (ACE), the concession agreement was marred by lack of transparency, fraud, and unfavourably negotiated terms for Uganda. The contract guaranteed Umeme a 20% annual return on investment, payable in US dollars, which the Committee considered excessive. Furthermore, the report found that Umeme's reported distribution losses were inflated from 28% to 38%. This led to Umeme being overcompensated by the government to the tune of US $43 million.

Efforts to annul the contract with Umeme were dashed when the GoU confronted the prospect of having to pay a large compensation package. The 2005 agreement included a Buyout Clause, which stipulated that if the concession was not renewed or was terminated, the government would be required to compensate Umeme for “unrecovered investments” particularly in long-term capital expenditures made during the life of the concession.

The ending of the 20-year Concession has opened up a legal battle between Umeme and the GoU. The 60% foreign-owned entity is asking for US $234 million in compensation for “unrecovered investments” under the Buyout Clause. The GoU asked the Auditor General to conduct a special audit to verify this amount. The Auditor General’s report put the figure at $118 million, roughly half of what Umeme is demanding. The Ministry of Energy accepted the Auditor General’s figure and rejected Umeme’s earlier claim for US $234 million. The GoU needed to take out a commercial loan to pay the US $118 million.

On April 11th, Umeme filed a formal Notice of Dispute. It now seems likely that the case will be taken to the London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA), a body that has frequently ruled in favor of multinational companies in similar disputes with sovereign governments.

Unions have long been concerned that external arbitration often overrides national law; the proceedings lack transparency, and there is no right to appeal. The outcome of this case could mark an important reference point for governments aiming to reclaim their energy sovereignty and policy independence. Private interests in Africa will hope the Court’s decision will discourage re-nationalisation efforts. The international trade union movement must be on full alert. A behind-closed-doors court in London should not be allowed to challenge key policy decisions made by sovereign governments.